Gamarjoba (hello) from the magical land of mountains, cheese, and amber wine - Georgia!

If you’ve been following my Instagram lately, you know that my family and I have been traveling through Georgia (or Sakartvelo as it’s called here) for the past 5 weeks. It’s been an absolute whirlwind as we made our way through all 9 of the country’s regions + Adjara (which is considered an autonomous republic). We returned to Tbilisi yesterday and have one more week to soak up the city before we head back home.

My last post was about trusting in the timing of my life and, well, I don’t think I could’ve timed this trip and itinerary more perfectly. It really feels like the stars aligned on this one. My mind is reeling with so much inspiration - not only in terms of recipes I want to share with you all, but also the stories of all the cool things happening here (and the even cooler people behind them!).

But alas, I’m still on the road and have very little time to get into things right now, so instead I will leave you here with an essay I wrote about the dedakatsi (mother-men) of Georgia a few years ago for

’s book Why We Cook: Women on Food, Identity, and Connection. I first heard of the term fromUkrainian London-based chef and author Olia Hercules (who I just happened to meet in Tbilisi a few weeks ago!). Not surprisingly, the concept of dedakatsi has come up in conversation many times these past few weeks and I’m starting to think there’s something worth delving deeper into here. I’ll leave it at that :)Dedakatsi

From her perch atop the Sololaki ridge, Georgia’s most famous woman—and protector—proudly stands 65 feet tall and looks down over the ancient city of Tbilisi. Her left hand lifts a bowl of wine in greeting, and her right hand grips a sword in warning. Named Kartlis Deda, or “Mother of Georgia,” she was erected in 1958 as an embodiment of the national character: a hospitality that knows no bounds and a fierce pride in the country’s freedom and strength. For decades, the monument has also stood as a reminder to all women of their familial and national duties to provide for and protect their home.

Seeing women as devoted caretakers above all else is a concept deeply rooted in the Georgian patriarchal narrative, even today. But this imperative was brought to a whole new level during and following World War Two, when women had to take on the role of breadwinner while their husbands were away fighting. Thousands of men never came home, and the ones that did returned physically and mentally maimed, unable to fully or properly care for their families again. What other options did these mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters have but to continue carrying out their familial duties—even if this responsibility verged on the self-sacrificial? So, they labored on—cooking, cleaning, working, and persevering—and eventually these resilient women became known as the dedakatsi, or “mother-man.”

This phenomenon continued through the remainder of the twentieth century as social and economic turmoil racked the Soviet-bloc country. The women of this new generation were forced to find creative ways to bring in income—hawking goods such as secondhand clothes or homemade cakes on the streets, for example—while men continued to sit at home without jobs. Time and time again, in response to male defeatism, these determined dedakatsebi rose to the challenge.

I first heard the term “mother-man” while listening to an interview with London-based chef and author Olia Hercules discussing her cookbook Kaukasis, the Cookbook: A Culinary Journey through Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Beyond. She described coming across the concept and history of the dedakatsi. “For me,” said Hercules, who was born in Ukraine, “it was the most incredible discovery. I met so many women like that who have nothing to do with the feminist movement. They don’t know what it is, but they are that—personified.”

Hercules reminded me of the strong, independent women in my own life: my mother and her six sisters, who were born and raised in Tbilisi. They learned from a very early age how to get by and be content with very little; that life owed them nothing; and that hard work always paid off. As they grew older, each sister followed her own path, but their familial ties and sense of obligation to each other remained strong. Eventually, five of them (including my mother) fled the country together in the chaotic wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

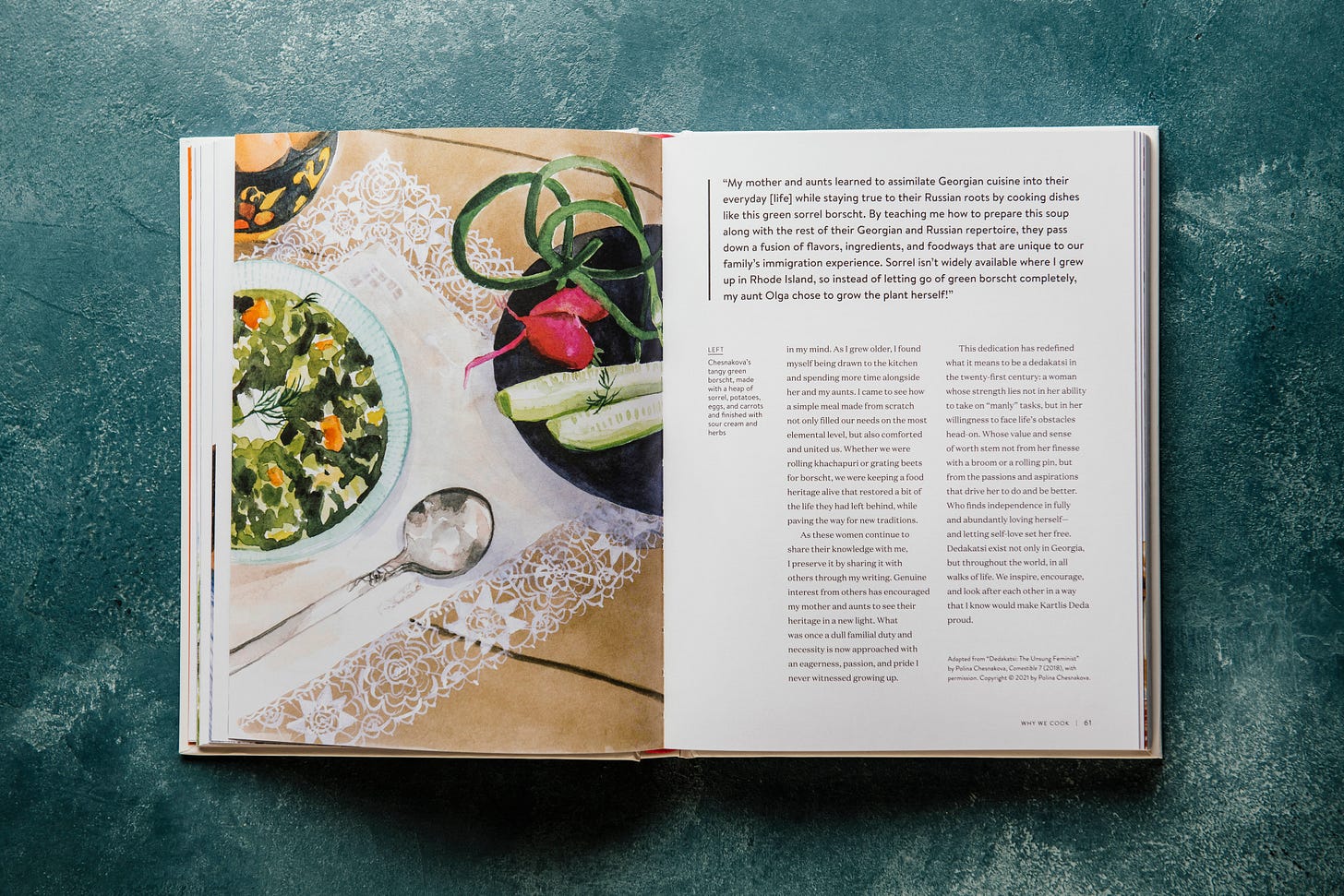

These dedakatsebi taught me perseverance, willpower, and sisterhood. But the most formative lesson I gleaned from them was the power of food. Images from my childhood of my mother standing at the stove stirring a big pot of stew or at the counter chopping cilantro will forever be ingrained in my mind. As I grew older, I found myself being drawn to the kitchen and spending more time alongside her and my aunts. I came to see how a simple meal made from scratch not only filled our needs on the most elemental level, but also comforted and united us. Whether we were rolling khachapuri or grating beets for borscht, we were keeping a food heritage alive that restored a bit of the life they had left behind, while paving the way for new traditions.

As these women continue to share their knowledge with me, I preserve it by sharing it with others through my writing. Genuine interest from others has encouraged my mother and aunts to see their heritage in a new light. What was once a dull familial duty and necessity is now approached with an eagerness, passion, and pride I never witnessed growing up.

This dedication has redefined what it means to be a dedakatsi in the twenty-first century: a woman whose strength lies not in her ability to take on “manly” tasks, but in her willingness to face life’s obstacles head-on. Whose value and sense of worth stems not from her finesse with a broom or a rolling pin, but from the passions and aspirations that drive her to do and be better. Who finds independence in fully and abundantly loving herself—and letting self-love set her free. Dedakatsebi exist not only in Georgia, but throughout the world, in all walks of life. We inspire, encourage, and look after each other in a way that I know would make Kartlis Deda proud.

Excerpted from Why We Cook: Women on Food, Identity, and Connection by Lindsay Gardner. Copyright © 2021 by Lindsay Gardner.

Art by Lindsay Gardner (if you haven’t already, go check out her newsletter Constellations). Used by permission of Workman Publishing Co., Inc., New York. All rights reserved.

As my trip comes to an end and I start planning future newsletter posts (and special paid subscriber content!!), I’d love to hear from you! What kind of Georgian-inspired recipes, stories, travel guides (?) do you want to see here? Wonder how we managed to pull off this trip with a 2 1/2 year old? What other countries of the Caucasus and Eastern Europe do you want to read about? If you know someone who might be interested in this post or newsletter - make sure to send it over to them! Madloba (thank you) in advance <3

I love this: “Who finds independence in fully and abundantly loving herself—and letting self-love set her free. Dedakatsebi exist not only in Georgia, but throughout the world, in all walks of life. We inspire, encourage, and look after each other in a way that I know would make Kartlis Deda proud.”

Very inspiring! Thank you for sharing, Polina! Enjoy those days in Georgia and wishing you safe travels back to RI!